De Europese Commissie blaakt van ambitie om de invoering van duurzame energie te bevorderen om een low-carbon economy te realiseren. Met grote regelmaat publiceert zij even lijvige als ondoordringbare rapporten en mededelingen, die de indruk wekken van koortsachtige activiteiten ter zake. Immers, de EU wil nog steeds een voortrekkersrol spelen op dit gebied.

Wat is het effect van dat alles? Misschien dat de EU er de laatste jaren in is geslaagd iets minder uitstoot te realiseren. Dat is moeilijk na te gaan, want niettegenstaande vrome en vaak herhaalde wensen van verbetering van transparantie, blijven de cijfers over de actuele CO2-uitstoot van de EU zo doorzichtig als koffiedik.

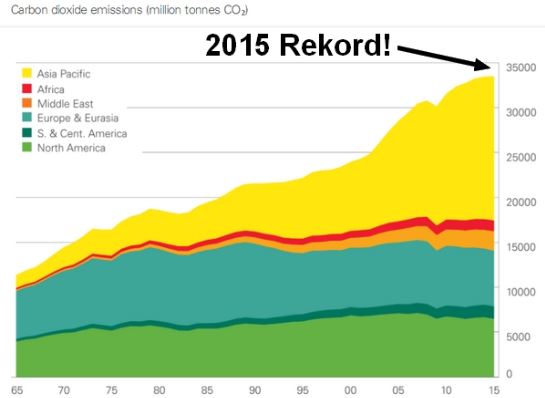

Maar ondanks alle mooie beloften op de steeds maar weerkerende klimaatconferenties is de uitstoot wereldwijd toch behoorlijk toegenomen. Biljoenen aan klimaatbeleid hebben niet kunnen verhinderen dat de mondiale CO2-uitstoot in 2015 een record bereikte.

Dat belet de EU niet om in haar eentje de planeet te willen redden van die verzengende opwarming van de aarde, die maar steeds niet wil komen.

Wie de rijstebrij aan rapporten van het Energie-commissariaat van de EU probeert te lezen, wordt vergast op een lawine aan initiatieven, fondsen, samenwerking met organisaties en sectoren binnen de EU, samenwerking met landen buiten de EU (die weinig economisch gewicht hebben), conferenties, dialoog, evaluaties, monitoring, enz. enz. Maar wat al die kippendrift tot op heden heeft opgeleverd blijft onduidelijk. Behalve dat die bakken met geld kost.

Zoals reeds opgemerkt, ambtelijk EU-proza is vaak ondoorgrondelijk. Het is daarom ook toe te juichen dat er deskundigen zijn die zich als schriftgeleerden opwerpen om ons duidelijk te maken dat dat wat er staat toch eigenlijk iets anders betekent. John Constable, die als energieredacteur aan de ‘Global Warming Policy Foundation’ (GWPF) is verbonden, is er zo een.

Onder de titel, ‘Is the European Commission Waking up to Electricity Consumer Pain?’ schreef hij:

Specialists have long known that the system management cost of even medium and certainly higher levels of non-despatchable renewable electricity, such as wind and solar, was no less important in magnitude than the income support subsidies required to motivate capital investment in the generating equipment. General awareness of this fact is now rising, and the wisdom of socializing those costs is under question (See for example, Jonathan Ford, “The Hidden Costs of Renewable Power” Financial Times (21.08.17)). When a problem of this nature is socialized it becomes nobody’s problem, and no one will address it, with all parties quite rationally preferring to sit on their hands and allow the consumer to bear the cost. ….

De oplossing dient te worden gezocht in méér marktwerking.

Pressure is now growing to force these changes through, with even the European Commission recognizing that something has to change. A recent communication from the EC to the European Parliament (zie hier), suggests, obliquely as is ever the case the EU, that renewable generators will no longer be treated with kid gloves, and must expect increasingly to operate by the same rules that bind other generators. The statements require interpretation. When the Commission writes that “market rules will be adapted to allow renewable producers to fully participate and earn revenue in all market segments, including system services markets” (p. 8) they mean renewables can no longer expect to be shielded from the rough and tumble of the market place. When they write that “Priority dispatch will remain in place for existing installations, small-scale renewable installations, demonstration projects” (p. 8) they mean that new installations will not have priority dispatch, and must bid like any other generator. And when the Commission writes that “curtailment of renewables should be kept to a strict minimum” this remark must be seen in the context of the previous observations, and so interpreted as meaning that compensated curtailments within the market must be minimized and renewable generators must be increasingly responsible for their own presence in the market.

All this is very sensible, in so far as it goes, but whether any of it will be carried through into practice remains to be seen. One has to assume that the industries concerned are, lobbying strongly in Brussels to ensure that these reforms are introduced as slowly as possible and in as weak a form as may be. They will almost certainly have some degree of success.

Rapid progress is, unfortunately, not be expected, but there will be progress because there must. The European Commission’s own press release was entitled “Commission proposes new rules for consumer centred clean energy transition” [https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/news/commission-proposes-new-rules-consumer-centred-clean-energy-transition]. The Commissions idea of a “consumer centred” energy market is probably not quite Milton Friedman’s, but it would be obtuse and ungrateful not to acknowledge that even the modest degree of rebalancing probably implied here is a step in the right direction. Producer interests have simply had it too easy for far too long. …

This is the writing on the wall. Priority access will have to be denied to all renewable generators, not just new entrants. Renewable generators will have to take a large part of the risk of curtailment, and cannot expect non-market compensation. In summary, renewables will have to pay “their fair share of network and system costs”. The special terms on which renewables have hitherto operated are coming to an end, slowly but surely. The cost of managing their uncontrolled output is about to become their problem, not something that can be silently shuffled on to electricity bills.

Aldus John Constable.

Lees verder hier.

0 reacties :

Een reactie posten